One of the world’s most comprehensive and progressive women’s human rights instruments, the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol) was adopted by Heads of State and Government in Maputo, Mozambique, on 11 July 2003. To commemorate the 19th Anniversary of the Maputo Protocol, the SOAWR Coalition is celebrating 19 reasons why the Protocol benefits the diversity of African women and girls, their lived realities, communities and governments.

Go to:

1. African Union Member States

Whilst the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights provides a foundational framework for domesticating human rights within national legislations, only one out of the more than sixty articles in the African Charter makes specific reference to women. For example, the Charter does not explicitly define discrimination against women and lacks guarantees to the rights to consent to marriage and equality in marriage.

The Maputo Protocol notes the concern “that despite the ratification of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other international human rights instruments by the majority of States Parties, and their solemn commitment to eliminate all forms of discrimination and harmful practices against women, women in Africa still continue to be victims of discrimination and harmful practices.”

Subsequently, the Maputo Protocol, which resulted from years of activism by women’s rights supporters in the region, has reinvigorated the African Charter’s commitment to women’s equality by adding rights that were missing from the Charter and clarifying governments’ obligations concerning women’s rights.

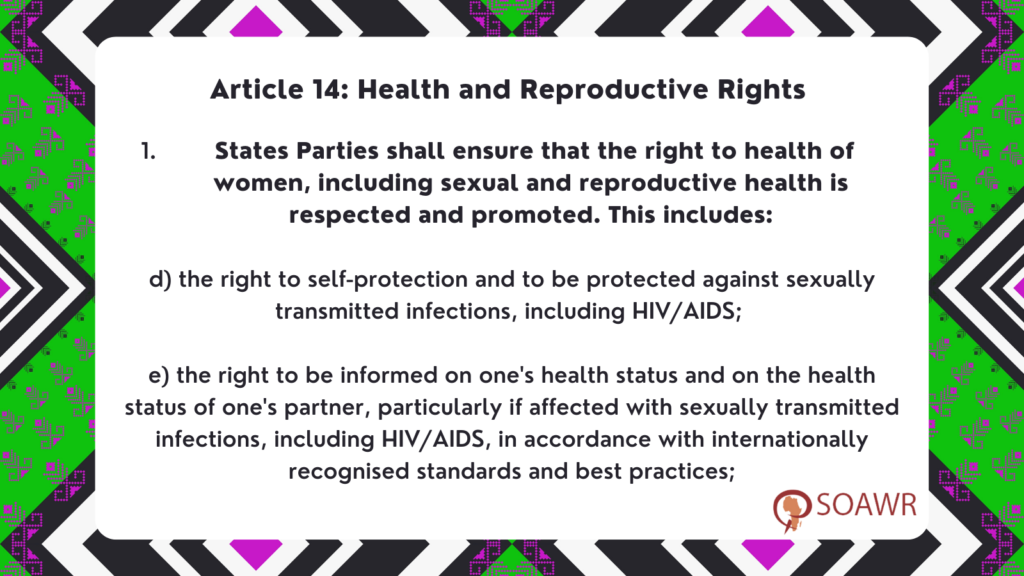

2. Women Living with HIV/AIDS

The Maputo Protocol is the only treaty to specifically address women’s rights in relation to HIV/AIDS and to identify protection from HIV/AIDS as a key component of women’s sexual and reproductive rights. No global human rights instrument other than the Maputo Protocol has expressly articulated the standards governing women’s rights and states’ duties concerning the HIV/AIDS pandemic:

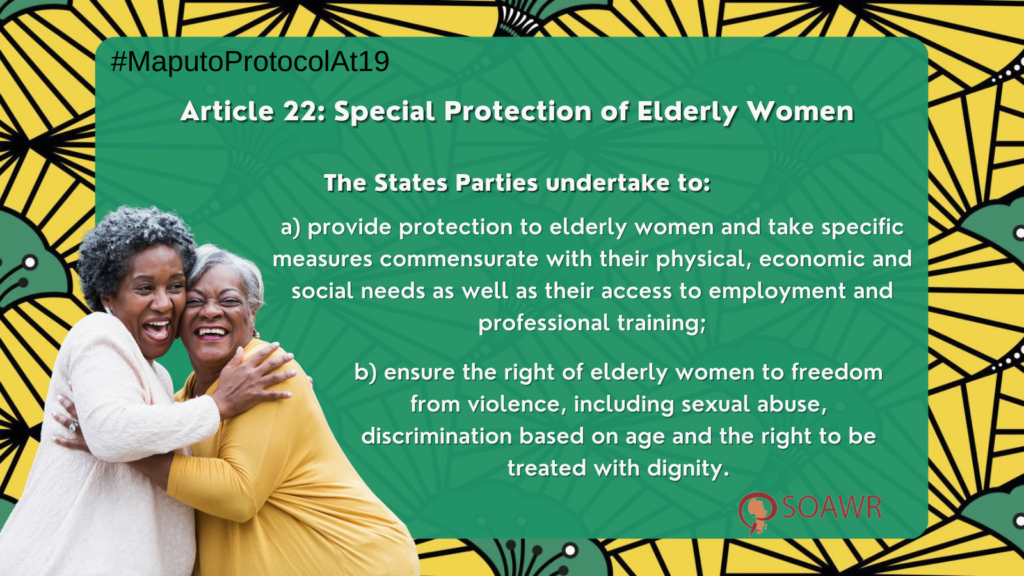

3. Elderly Women

The research, though scant, shows that abuse is a deep-seated social problem threatening the well-being of older people in Africa (Chane & Adamek, 2015; Mba, 2007; Tawiah, 2011). Abuse of older people in this region includes accusations of witchcraft, for which older people are assaulted, ostracized, and even killed (Atata, 2019; Malmedal & Anyan, 2020).

A remarkable feature of the Maputo Protocol is its recognition that even among women, some are more vulnerable due to several factors, including age. It dedicates an entire article to rights explicitly guaranteed to elderly women and their lived realities.

4. Refugees, Asylum Seekers & Internally Displaced Persons

In 2021, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported that “for Refugees, sub-Saharan Africa hosts more than 26% (over 18 million) of the world’s refugees. The number of refugees has soared over the years, partly due to the ongoing crises in the Central Africa Republic, Nigeria, South Sudan and Burundi. Initially localised in the Horn of Africa, refugee camps are now springing up in all other sub-regions, especially in West and Southern Africa. Globally, Africa has the largest number of IDPs who outnumber refugees 5:1.”

Preceding the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa” (better known as the Kampala Convention), which came into effect in 2012, the Maputo Protocol consists of a variety of rights and measures specifically relating to refugees, asylum seekers and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs):

- Article 4 mandates governments to ensure that women and men enjoy equal rights in terms of access to refugee status determination procedures and that women refugees are accorded the full protection and benefits guaranteed under international refugee law, including their own identity and other documents.

- Article 10 outlines that States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure the increased participation of women in:

- local, national, regional, continental and international decision-making structures to ensure physical, psychological, social and legal protection of asylum seekers, refugees, returnees and displaced persons, in particular women;

- all levels of the structures established for the management of camps and settlements for asylum-seekers, refugees, returnees and displaced persons, in particular, women;

- Article 11, 3: States Parties undertake to protect asylum seeking women, refugees, returnees and internally displaced persons against all forms of violence, rape and other forms of sexual exploitation and to ensure that such acts are considered war crimes, genocide and/or crimes against humanity and that their perpetrators are brought to justice before a competent criminal jurisdiction.

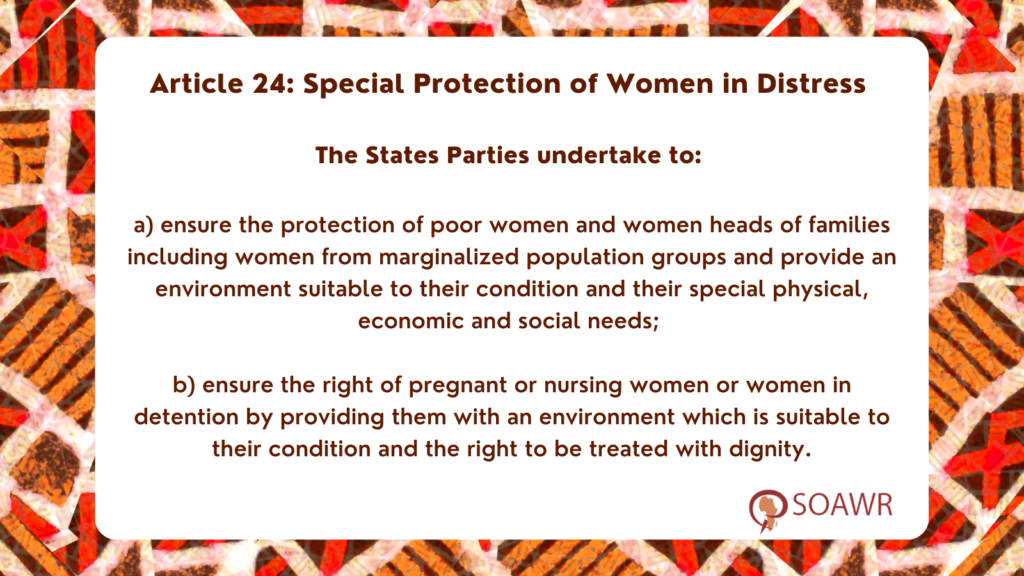

5. Women in Distress

Under the Protocol, the Member States undertake to protect women in distress:

The Maputo Protocol in Action

Rights relating to Articles 2, 3 & 24 were used in a 2015 Kenyan High Court Case: MAO & Another v. Attorney General & Others

issue

Detention of indigent women for inability to pay the cost of maternity services in hospitals. The first petitioner was a HIV-positive mother of six who worked as a casual labourer, and the second petitioner was a mother of five who worked as a hair dresser but did not have a fixed income. Both women were impoverished and could not meet the cost of necessities for themselves and their children. Both the petitioners delivered babies in the hospital but were unable to cover the cost of hospital expenses for delivery. As a result, they were detained by the hospital until they could somehow raise money to pay the hospital bill. After these cases, the Kenyan government introduced a new policy whereby maternity fees would no longer be charged in public hospitals. However, no action was taken to implement this initiative.

Decision

The Court held that Kenya had “not fulfilled its constitutional and international obligations with regard to the right to health, the prevention of discrimination, the right to dignity and the prevention of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment with respect to women seeking reproductive health services”. It declared the detention unlawful and arbitrary and ordered the government to take necessary steps to protect patients from arbitrary detentions in healthcare facilities. It also awarded damages to the petitioners.

6. African Men

Many people falsely assume that the Maputo Protocol and indeed any women’s rights treaty or initiative do not benefit them or even come at a cost to them.

However:

- A World Health Organisation report found that “men’s health was poorer in more gender-unequal societies – the sexual division of labour harms men as well as women”.

- In an academic study asking, ‘What’s in it for Men?’, men in more gender-equal societies were found to be half as likely to be depressed, less likely to commit suicide, have around a 40% smaller risk of dying a violent death and even suffer less from chronic back pain.

- As Human Rights Careers reports, “A man who is perceived as “feminine” is not a “real man” when gender inequality exists. This perception leads to toxic masculinity, which is destructive and harmful to everyone. With gender equality, men have more freedom about how they express themselves. It extends into the career field, as well, since no job is considered “for women only.” Men receive parental leave and family time without discrimination. Increased freedom of expression and flexible work choices leads to happiness. With gender equality, men don’t face as much pressure to fit a stereotype.”

Whilst some African men benefit from male privilege, there is more to be gained in implementing the Maputo Protocol.

7. Women with Disability

As part of the Leave No Woman Behind project, Global Call to Action Against Poverty (GCAP) published a 2021 report that summarised, “Women and girls with disabilities in Africa carry multiple burdens of discrimination, by virtue of their age, gender and their disability. Compared with men with disabilities, globally, women with disabilities are three times more likely to have unmet needs for health care, three times more likely to be illiterate, two times less likely to be employed and two times less likely to use the Internet. Women with disabilities are at a two to four times higher risk of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) than those without disabilities.”

Governments must develop legislation, policy and infrastructures specifically tailored to these needs. Preceding the African Union 2018 Protocol for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the Maputo Protocol sets out two particular obligations for states:

8. Transgender persons

The Maputo Protocol guarantees rights specifically for African women, tailoring these to their unique lived realities and needs. The Protocol inclusively defines ‘women’ as “persons of female gender” as opposed to limiting these rights to those of the ‘female sex’.

For African transgender and gender non-conforming persons, the Maputo Protocol lays the important legal groundwork for more expansive human rights to be implemented, such as:

- Article 2c calls for State Parties to “integrate a gender perspective in their policy decisions, legislation, development plans, programmes and activities and in all other spheres of life”.

- Article 8d mandates State Parties to ensure “that law enforcement organs at all levels are equipped to effectively interpret and enforce gender equality rights”

- Article 12e demands State Parties to “integrate gender sensitisation and human rights education at all levels of education curricula including teacher training.”

- Article 19a requires State Parties to “introduce the gender perspective in the national development planning procedures.”

9. Widows

According to the World Bank, one in ten African women above the age of 14 is widowed.

A Lead Economist at the World Bank, Dominique van de Walle, argued that providing widows with a secure foothold in society is central to the broader struggle for gender equality, stating “In much of Africa, marriage is the sole basis for women’s access to social and economic rights, and these are lost upon widowhood”.

Some may even lose their children to the husband’s lineage. Broader patterns of gender inequality add to the heavy burden on women’s shoulders. They are shut out of labor markets, have fewer productive assets, and bear greater responsibility for caring for children and the elderly.

In some regions, young widows are encouraged to remarry. Levirate marriage—a tradition in which a widow marries a relative of the deceased husband—provides a modest safety net. Still, the remarried widow often occupies an inferior position in the new household. In Senegal, for example, levirate marriage is associated with the lowest consumption levels for previously widowed women. These marriages can act as a poverty trap for those who cannot refuse due to a lack of means. In other settings, widows and divorcees may be shunned, ostracised, and dispossessed.

In addition to an entire article being dedicated to the rights of widows, Article 21a of the Maputo Protocol guarantees widows’ rights to inheritance: “A widow shall have the right to an equitable share in the inheritance of the property of her husband. A widow shall have the right to continue to live in the matrimonial house. In case of remarriage, she shall retain this right if the house belongs to her or she has inherited it”.

10. African Children, especially Girls

The Protocol ensures a variety of rights particular to African children:

- The Protocol specifies 18 as the minimum age of marriage, affirming girls’ and women’s right to be protected from child marriage (Article 6b).

- States Parties must take all necessary measures to ensure that no child, especially girls under 18 years of age, take a direct part in hostilities and that no child is recruited as a soldier (Article 11, 4).

- Governments must especially protect the girl-child from all forms of abuse, including sexual harassment in schools and other educational institutions and provide for sanctions against the perpetrators of such practices (Article 12, 1c).

- States are to promote the enrolment and retention of girls in schools and other training institutions (Article 12, 2c).

- Lastly, Member States must introduce a minimum age for work and prohibit the employment of children below that age, and prohibit, combat and punish all forms of exploitation of children, especially the girl-child (Article 13g).

Following a ruling by the High Court in 2016, the Tanzania Court of Appeal upheld a landmark ruling against child marriage in 2019. The case challenged the constitutionality of sections 13 and 17 of the Marriage Act, which set the minimum age of marriage for girls at 15 years and 18 years for boys.

The High Court had ruled that marriage under the age of 18 was illegal and directed the Government of Tanzania to raise the minimum age of marriage to 18 for both boys and girls within one year. The Court referred to Article 6 of the Maputo Protocol which sets the minimum age of marriage at 18.

11. Divorcees

Based on the limited data available, as of 2018, 6% of all African women above the age of 14 are divorced and many more have been divorced at some point in their lifetime. The Maputo Protocol provides comprehensive obligations for governments:

The Maputo Protocol in Action

Uganda Association of Women Lawyers & Others v. Attorney General [2004] UGCC 1 (Constitutional Court of Uganda)

issue

Uganda’s Divorce Act allowed husbands to obtain a divorce if they proved adultery by the wife. However, for a wife, it was not enough to prove adultery. She had to prove aggravated adultery on the husband's (which was adultery in addition to other offences like incest, bigamy, cruelty etc.). The petitioners challenged the constitutional validity of these provisions on the ground that they discriminated against women and perpetuated inequality between the sexes.

Decision

The Court found that the impugned provisions of the Divorce Act were discriminatory towards women, and hence, unconstitutional. Damages were awarded to the petitioners.

This decision of the Ugandan Constitutional Court was pronounced before the Maputo Protocol came into force (the Protocol required 15 ratifications by AU member States before it could come into effect). However, the case still recognised the Maputo Protocol as an important regional instrument for the advancement of the rights of women.

In addition to this case, in a number of other cases before Kenyan and Malawi Courts, Article 7(d) of the Maputo Protocol has been cited either by the parties or by the Court in relation to the issue of division of matrimonial property.

These cases include:

- ZWN v. PNN [2012] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

- CMN v. AWM [2013] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

- JAO v. NA [2013] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

- Kishindo v. Kishindo [2014] MWHC 2 (High Court of Malawi)

- ANM v. DMN [2015] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

- Rael Mbithe Mwangangi v. James Mutual Musembi [2015] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

- PAW-M v. CMAW-M [2016] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

- AWM v. PGM [2016] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

- MWW v. SWM [2017] eKLR (High Court, Kenya)

12. Women in Rural Areas

Women make up more than 50% of Africa’s population and 80% reside in rural areas. Over 60% are employed in rural areas in the agriculture sector.

Yet, as Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, then United Nations Under-Secretary-General and executive director of UN Women, stated in 2018, “If there’s anyone left behind, it is women and girls in rural areas” and went on to acknowledge the need “to take those at the back of the line to the front of the line.”

Encouragingly, the Maputo Protocol specifies two rights to contribute to this, requiring State Parties to:

- provide adequate, affordable and accessible health services, including information, education and communication programmes to women, especially those in rural areas (Article 14, 2a).

- promote women’s access to credit, training, skills development and extension services at rural and urban levels in order to provide women with a higher quality of life and reduce the level of poverty among women (Article 19d).

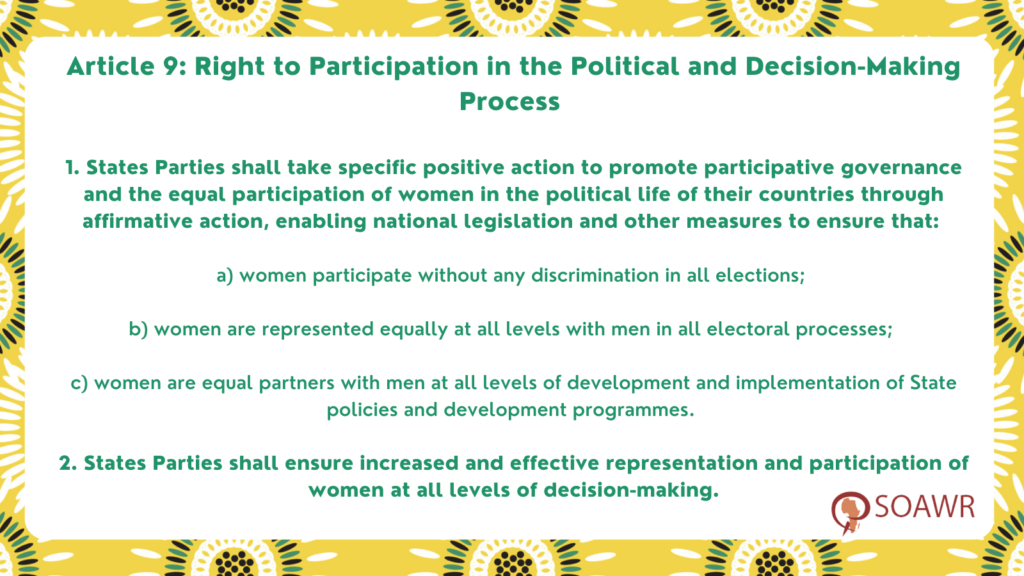

13. Women’s Participation in Politics, Decision-making & Leadership

The Maputo Protocol goes into detail regarding African Union Member States’ mandates to ensure and promote African women’s equal participation in all political and decision-making processes:

Due to the multi-level benefits of maintaining governments and societies which are committed to involving all stakeholders, Article 9 not only benefits African women but also African parliaments and wider society. For example, studies have shown that the higher the proportion of women in parliament, the lower the likelihood that the state carries out human rights abuses. Rwanda serves as a model example, with its global number one ranking for women’s political involvement and representation (86% of Rwandan women are active in the national labour market, they hold 55% of government cabinet positions and 61.3% of seats in Rwanda’s parliament).

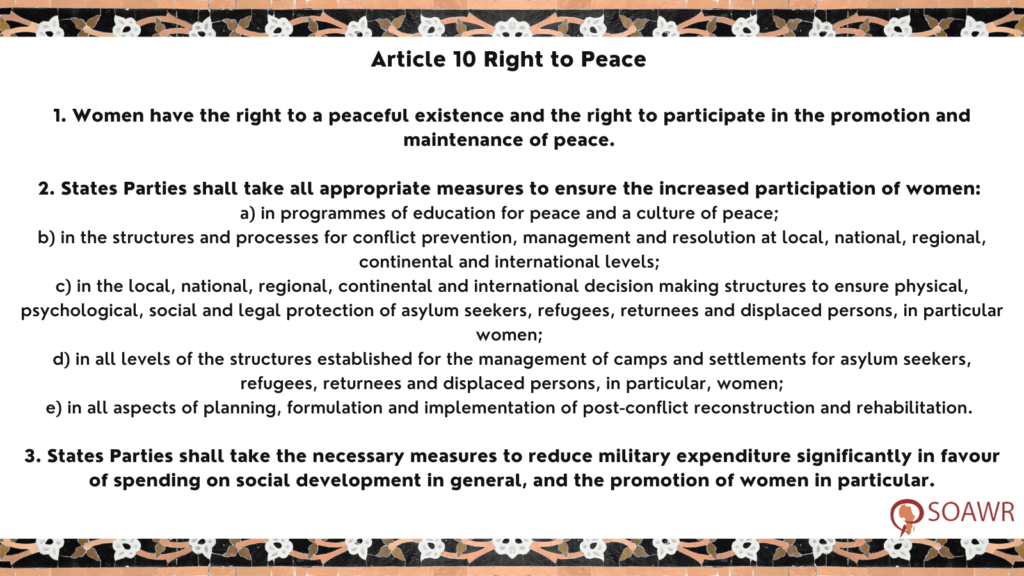

14. Peaceful Societies

Article 10 of the Maputo Protocol clarifies women’s rights to a peaceful existence and involvement in decision-making and infrastructure relating to peace. Especially poignant and pragmatic is the third sub-article which states that governments “shall take the necessary measures to reduce military expenditure significantly in favour of spending on social development in general, and the promotion of women in particular.”

Whilst others might argue that the 21st century demands extensive defence budgets, contemporary academic research has shown that where women are more empowered in multiple spheres of life, countries are less likely to go to war with their neighbours, to be in bad standing with the international community, or to be rife with crime and violence within their society. It is also evident that gender equality is a better indicator of a state’s peacefulness than other factors like democracy, religion or GDP.

Another study looked at data on international crises over four decades. It found that as the percentage of women in parliament increases by 5%, a state is 5 times less likely to use violence when faced with an international crisis.

15. Gender-Based Violence & Sexual Assault Survivors (Potential & Realised)

The Protocol goes beyond existing global and regional treaties by affording specific legal protection against gender-based violence in both the public and private sphere, including domestic abuse and marital rape. The Protocol significantly advances women’s rights by relocating everyday abuses in the private sphere of the home to the public realm of rights violations for which states must be held accountable.

Secondly, the Protocol is unique among global human rights treaties in expressly articulating girls’ and women’s right to be protected from sexual harassment as a critical component of their right to equality in education. The Maputo Protocol also affirms women’s right to be free from sexual harassment as a basic social and economic right and as a key component of their right to work.

Additionally, the Maputo Protocol represents the first time that an international human rights instrument has explicitly articulated a woman’s right to abortion. The right to abortion includes when pregnancy results from sexual assault, rape, or incest; when continuation of the pregnancy endangers the life or health of the pregnant woman; and in cases of grave fetal defects that are incompatible with life.

The Maputo Protocol in Action

In December 2020, the High Court of Kenya issued a historic decision that found the Government of Kenya liable for failure to investigate and prosecute cases of sexual and gender-based violence that happened during the post-election violence of 2007. Eight survivors filed the lawsuit with support from non-governmental organisations seeking accountability and redress for these violations.

The Court found the government violated several human rights instruments, including the Maputo Protocol and ordered the government to pay compensation to four survivors amounting to KSH 4 million (approximately 40,000 USD) per survivor.

16. Women in the Informal Sector

Women constitute 89% of the workforce in the informal economies in sub-Saharan Africa. Whilst the Maputo Protocol stipulates many economic and social welfare rights throughout, there are two provisions specific to women working in the informal sector whereby State Parties must:

- create conditions to promote and support the occupations and economic activities of women, in particular, within the informal sector (Article 13e),

- establish a system of protection and social insurance for women working in the informal sector and sensitise them to adhere to it (Article 13f).

The significance of these rights has become increasingly evident through the shocks and continual economic challenges brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic.

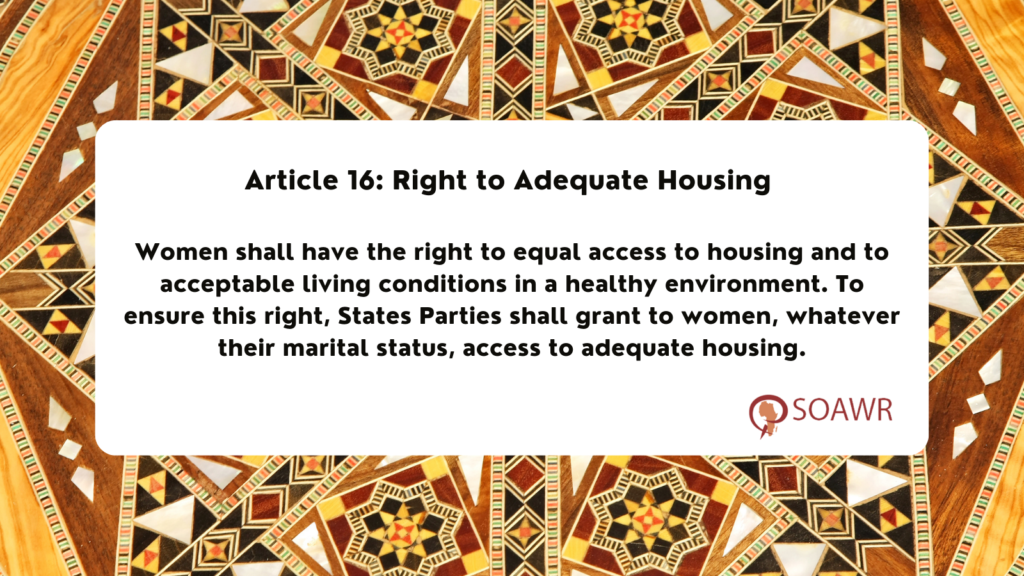

17. People without Homes

As Financial Sector Deepening (FSDAfrica) reports, guaranteeing women’s right to adequate housing has positive flow-on effects for both women and their wider community:

“The consequences of good housing are far-reaching: the quality of housing impacts on its residents’ health and safety, their ability to function as productive members of society, and their sense of well-being in their community. Good housing contributes to good health outcomes, provides protection from the elements and supports a family’s needs throughout its life cycle. These factors have a particular impact on women. The quality of the living environment impacts particularly on her day-to-day experiences and capacities to meet the needs of all who depend upon her.”

Importantly, the Maputo Protocol not only mandates that governments grant women access to adequate housing and a healthy environment, but goes on to specify that these rights are not dependent on marital status:

18. The African Diaspora and International Community

The Maputo Protocol, as seen in all its unique attributes discussed here, is a comprehensive, contextual and intersectional women’s rights treaty. Filling gaps in other regional and international human rights treaties, it serves as a model of best practice for the international community to learn from and an effective instrument for the international community to support. It is particularly poignant in the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade in the United States; in contrast, the Maputo Protocol presents the first articulation in an international human rights treaty, of a woman’s right to abortion in cases of rape, incest and where the continued pregnancy endangers the life of the mother. Subsequently, the Maputo Protocol has served as a key factor in many African nations codifying the right to abortion in domestic legislation and continues to do so – just less than two weeks ago, Sierra Leone moved to decriminalise medical abortions.

19. Traditional & Cultural Groups

While the Maputo Protocol contains similar provisions as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), it expands further legal protection for women. In particular, it takes a more nuanced approach to culture and tradition and explicitly acknowledges the positive role culture and tradition can play in women’s lives.

Significantly, the Protocol is the first international rights treaty to specifically call for prohibiting harmful practices, including female circumcision/female genital mutilation (FC/FGM). Simultaneously, it does not characterise all traditions and cultures as inherently anti-women or anti-progressive. The Protocol clarifies that the legal protection of tradition ends where discrimination against women begins and further provides, through Article 17, that “women shall have the right to live in a positive cultural context and to participate at all levels in the determination of cultural policies”. Additionally, “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to enhance the participation of women in the formulation of cultural policies at all levels”. These rights, ensuring that non-discriminatory and enriching cultural and traditional practices continue to thrive, benefit all.

This non-exhaustive list of 19 groups who benefit from the Maputo Protocol touches the surface of this treaty’s immeasurable holistic value. However, unfortunately, these rights and benefits are not yet ensured to the populations of: Botswana, Burundi, Egypt, Central African Rep., Chad, Eritrea, Madagascar, Morocco, Niger, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan.

As the SOAWR Coalition looks towards the 20th Anniversary in 2023, we will continue our Ratification Campaign, calling on these remaining twelve African Union Member States to accede to the Protocol to achieve universal ratification and more significantly, domestication and implementation.

Want to get involved?

Key sources which informed this blog:

- Caprioli, M. and Boyer, A. (2001) ‘Gender, Violence, and International Crisis‘, Journal of Conflict Resolution.

- Centre for Reproductive Rights (2006) The Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa: An Instrument for Advancing Reproductive and Sexual Rights.

- Equality Now (2021) 9 Ways the Maputo Protocol has Protected and Promoted the Rights of African Women and Girls.

- Global Call to Action Against Poverty (GCAP) (2021) ‘Leave No Woman Behind: Africa Report – Situation of Women and Girls with Disabilities’.

- Holter, O.G. (2014) ‘What’s in it for Men?: Old question, New data’, Men & Masculinities.

- Hudson, et al. (2012) ‘Sex and World Peace’, Colombia University Press.

- Melander, E. (2005) ‘Political Gender Equality and State Human Rights Abuse‘, Journal of Peace Research.

- Omondi, et al. and Equality Now (2018) ‘Breathing Life into the Maputo Protocol’

- O’Reilly, M. (2015) ‘Why Women? Inclusive Security & Peaceful Societies‘, Inclusive Security Report.

- Wamara, C.K. (2021) ‘Missing voices: older people’s perspectives on being abused in Uganda’, Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect.

- World Bank (2018) Invisible and Excluded: The Fate of Widows and Divorcees in Africa.