Source: African Arguments, analysis by Stephanie Musho.

18 years after African leaders adopted the Maputo Protocol, a progressive initiative by and for Africans, it is still yet to be fully implemented.

July is a significant month for African Women. On 31 July every year, the African Union (AU) leads the continent in celebrating African Women’s Day. More significantly, eighteen years ago on 11 July, African leaders converged in Mozambique and adopted what’s commonly referred to as the Maputo Protocol.

This legal instrument guarantees comprehensive rights to women. Among other things, it calls for the elimination of discrimination and harmful practices, rights to reproductive health and political participation, and the protection of women in armed conflict. It is a truly progressive initiative by and for Africans. Yet almost two decades later, it is yet to be fully implemented.

To date, 42 of 55 African states have ratified the Maputo Protocol. This has allowed human rights defenders in these countries to use it as a litigation tool. In 2020, for instance, Kenya’s High Court cited various international human rights instruments – including the Maputo Protocol – in finding the government liable for failing to investigate reported cases of gender-based assaults during the 2007-2008 post-election violence.

While many courts have been progressive in their application of the Protocol, however, many governments’ legislative and executive arms have created obstacles to it. Several states that require parliamentary approval to domesticate international treaty law into national law are yet to do so. This is perhaps unsurprising. In sub-Saharan Africa, women hold, on average, just 25% of legislative seats and patriarchal African states rarely prioritise women’s rights. There is an urgent need for more female political participation to ensure that women’s and girls’ rights are protected and promoted; only the wearer knows where the shoe pinches.

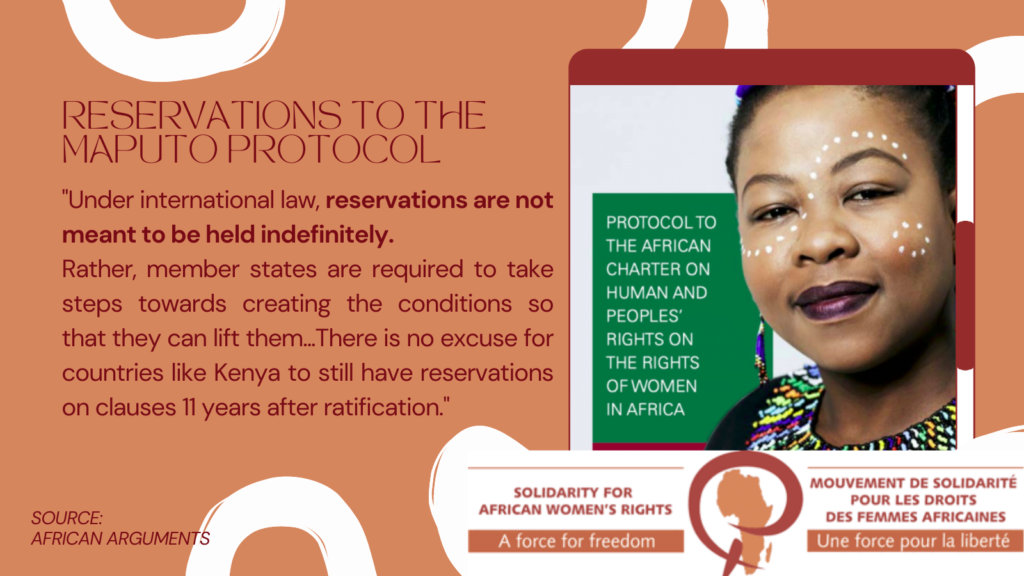

Another challenge for the full implementation of the Protocol is the issue of “reservations”. These legal caveats allow states to be party to a treaty while excluding the legal effect of one or more of its provisions. Certain African states have placed reservations on the Maputo Protocol, most commonly on articles 14(2) (c) and 10 (3) which provide the right to medical abortion and the reduction of military expenditure in favour of social development and the promotion of women. In Kenya, which ratified the Protocol in 2010 but with these reservations, 2,600 women and girls die every year from complications arising from unsafe abortions.

Under international law, reservations are not meant to be held indefinitely. Rather, member states are required to take steps towards creating the conditions so that they can lift them. Rwanda, for example, has removed its reservation on article 14 (2) (c) and initiated a law reform process alongside sensitisation campaigns and the training of healthcare providers. There is no excuse for countries like Kenya to still have reservations on clauses 11 years after ratification.

It is possible to prioritise women’s rights in Africa. This can start with the AU’s firm commitment to holding its partner states accountable to international treaty law, including the full implementation of the Maputo Protocol. While it could be argued that the AU cannot interfere with the sovereignty of African states or police them, it is worth noting that membership to the continental body is voluntary and that states routinely sign international law instruments, thus binding themselves.

International law can no longer be considered a suggestion hiding behind the guise of sovereignty. It is important and of great urgency that the AU shifts its reputation from a paper tiger to an efficient and effective intergovernmental organisation – one that holds its member states accountable to the obligations to which they commit. Until then, women and girls’ rights in Africa continue to be violated.

Share with your networks: